Did you know that July is Cell Phone Courtesy Month? I sure didn’t. At least, not until Free Spirit, the publisher of HOW RUDE!, asked me for some guidelines on polite cell phone behavior.

“You really think that’s necessary?” I said. “I’m always polite to my cell phone. Isn’t everyone?”

Free Spirit explained that, while most people treat their cell phones with kindness, some people use them in a manner that is insensitive or rude to others. Well, I was shocked.

SHOCKED!

SHOCKED!!

You could have knocked me over with a Blackberry. So I did some research and, sure enough, cell phone rudeness is rampant. In fact, in a HOW RUDE! Survey, teens, parents, and teachers cite inappropriate use of electronic devices as the manners violation that annoys them the most.

We’ve become a land of pointy-thumbed zombies—texting, swiping, and whispering sweet nothings into our phones. We chat with our wrists and speak into thin air—and no one calls the men in the white coats. Ask people about their significant other and they’ll show you their smartphone. One of these days we’ll learn that secondhand sound gives you cancer. And you gotta love all those stories about people so absorbed in texting that they walk into trees, stumble into fountains, and smash into doors. I have to admit my first reaction is “serves you right.” My second is “OUCH!”

With such a plague of telephonetic inetiquette, here are some basic rules for cell phone civility:

1) Turn off all beepers and ringers when you’re at an event or place where quiet and/or respect are required: houses of worship, libraries, concerts, plays, movies, lectures, funerals, restaurants, private dinners at someone’s home, etc. Silent ringers—the kinds that vibrate to give your thigh a thrill and let you know you have a call—are allowed as long as they’re not audible when vibrating. But you’re still not permitted to take the call. Instead, excuse yourself or slip out discreetly and call the person back.

2) Unwanted noise is not the only pollutant put out by cell phones. In a dark setting, light emitted by a cell phone can be an annoyance as well. So, if you are sitting in a movie theater, attending a séance, or hunkering down for a stakeout where light from your screen could give away your position, nix on the pix - els.

3) Recognize that people talking to themselves—and that’s how you appear to others, despite the piece of plastic growing out of your ear—are a distraction. Therefore, unless the call is of interest or relevance to everyone present (for example, a business negotiation or a loved one in common), take it to a private spot where your conversation won’t intrude on those of others.

4) Public restrooms are a place where people go to conduct their business. But not their cell phone business. Why not? Because it’s just too CREEPY, that’s why! So please stay off your phone in public bathrooms. Everyone will be relieved.

5) The sound of a ringing cell phone is annoying to others by definition. SO WHY DO PEOPLE CHOOSE THE LOUDEST, MOST OBNOXIOUS RINGTONES? (AND YES, I AM SHOUTING!) Choose a ringtone that isn’t going to rattle teeth or send shivers up one’s spine. And turn the volume down to the lowest setting that still allows you to hear it.

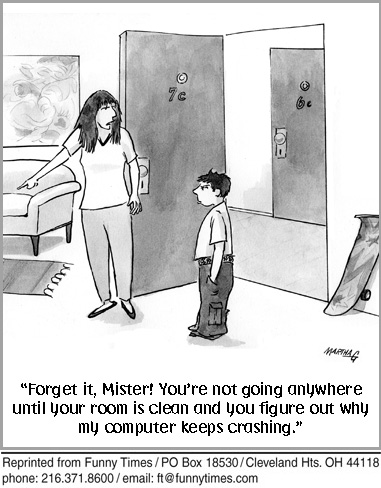

6) If you’re eating with others or attending a meeting, don’t place your mobile devices on the table. Glancing lovingly at your smartphone gives people the impression that you think it is more important than they are. And while that may be how you feel, you can’t show it! Be with the ones you’re with. As a wise teen said to her always-texting friends, “If you’re with me, be with me!”

7) Do not “hide” your phone on your lap. Just because it’s out of sight doesn’t mean people don’t know what you’re doing. They’ll see you looking down and think that you are either inordinately interested in your crotch or sending a text.

8) If you’re out with people and expecting an important call, let them know upfront that you’re going to have to take it and apologize in advance. When the call comes, excuse yourself and head to a private place.

9) No shouting please. People can hear you just fine if you talk in a regular voice.

10) Don’t make a scene. Bystanders do not need to witness your domestic disputes, percolating pathologies, or consumer outrages. On the flip side, if you’re the one who’s subjected to a 15-minute, best-performance-on-a-cell-phone meltdown, it’s only polite to applaud at its conclusion.

11) Sssshhhh. Now that phones can be used to listen to music, stream video, and play games, we have umpteen new ways to annoy people with unwanted noise. So turn down the volume.

12) It’s rude to run over a pedestrian because you were texting and driving. (If they were texting while crossing it increases the moral complexity of the situation, but you’ll still be the one in jail.) So always obey laws regarding cell phones when operating a vehicle. Use hands-free devices and never text while driving.

As Manners Guru to the Youth of America, I hereby declare that YOU control your phone. Not the other way around. Accordingly:

- You are permitted to let a call go to voicemail.

- You are permitted to stash your phone in a backpack, purse, pocket, or briefcase, and ignore texts and messages until later when you are ready to deal with them.

- You are permitted to turn your phone off. Yes, OFF. As in—off. Not on. Off. Will not ring. Will not distract. Will not disturb.

And finally, if you’re having lunch with someone who keeps texting, taking calls, and checking his phone, you may excuse yourself from the table, leave the restaurant, and send a text saying you’ve gone home.

(Bonus! Download The 24 Do’s and Don’ts of Cell Phone Etiquette (From the Minds of Genuine Teenagers), a free printable page from How Rude!® The Teen Guide to Good Manners, Proper Behavior, and Not Grossing People Out.)